Tim Walz: Vice Ball Coach in Chief

The Origin Story of the Democratic Vice Presidential Candidate is a Disney Movie and I Call Dibs

The beat of this newsletter is sports and the existential angst they cause. And if anybody has ever known sports induced existential angst, it was the football inclined students, faculty, and parents of Mankato West High School in August 1996.

The Mankato West Scarlets and their crosstown rival, the Mankato East Cougars, competed in the Class AAAA division and were members of Minnesota’s Big 9 Conference, an athletic association originally formed in 1928 to “promote athletic interests and good fellowship among schools.” Whatever that means.

There is no longer a conference championship because the conference’s membership no longer plays in the same district, but if there had been one, not even in their wildest dreams could they imagine winning it.

It’s been reported that going into the 1996 season, the school had lost 27 games straight. The head coach at the time, though, disputes this claim. He says it wasn’t that grim. They went 1-26.

In either case, considering your average high school football schedule consists of nine to ten games, it was safe to say that no one involved in the football program quite remembered what winning felt like. It was a vague notion. Something that happened to other people. Not them. They just lost.

Enter a curious teacher with a widow’s peak. National Guard artillery sergeant turned educator. A basketball coach, football coach, and teacher originally from Nebraska. He and his wife Gwen had just moved to the Mankato area to be closer to her family. She was an English teacher, and he joined her as a coworker at Mankato West. He didn’t teach Shakespeare, though. He was in the social studies department. Had a thing for maps, so naturally he taught geography.

His parents named him Tim Walz. The school’s head football coach, Rick Sutton, named him linebackers coach, and promoted him to defensive coordinator before the 1997 season.

Sutton was introduced to Walz by the school principal, who thought Walz would make a good addition to the football staff (it’s not as though it could get any worse). Sutton agreed after what he described to The Daily Beast as an informal interview.

“It was very obvious to me, right from the start[,] that Tim was the guy that we definitely want on our staff,” Sutton told the outlet. “We talked a lot about the process of getting to where we wanted to go… Staying positive on a day-to-day basis and keeping the overall goal in mind. Getting players to believe and trust.”

Walz didn’t have much trouble with “staying positive on a day-to-day basis” piece. He was one of those incredibly admirable and deeply annoying people who, as Los Angeles Chargers Head Coach Jim Harbaugh would put it, “attack each day with an enthusiasm unknown to mankind.”

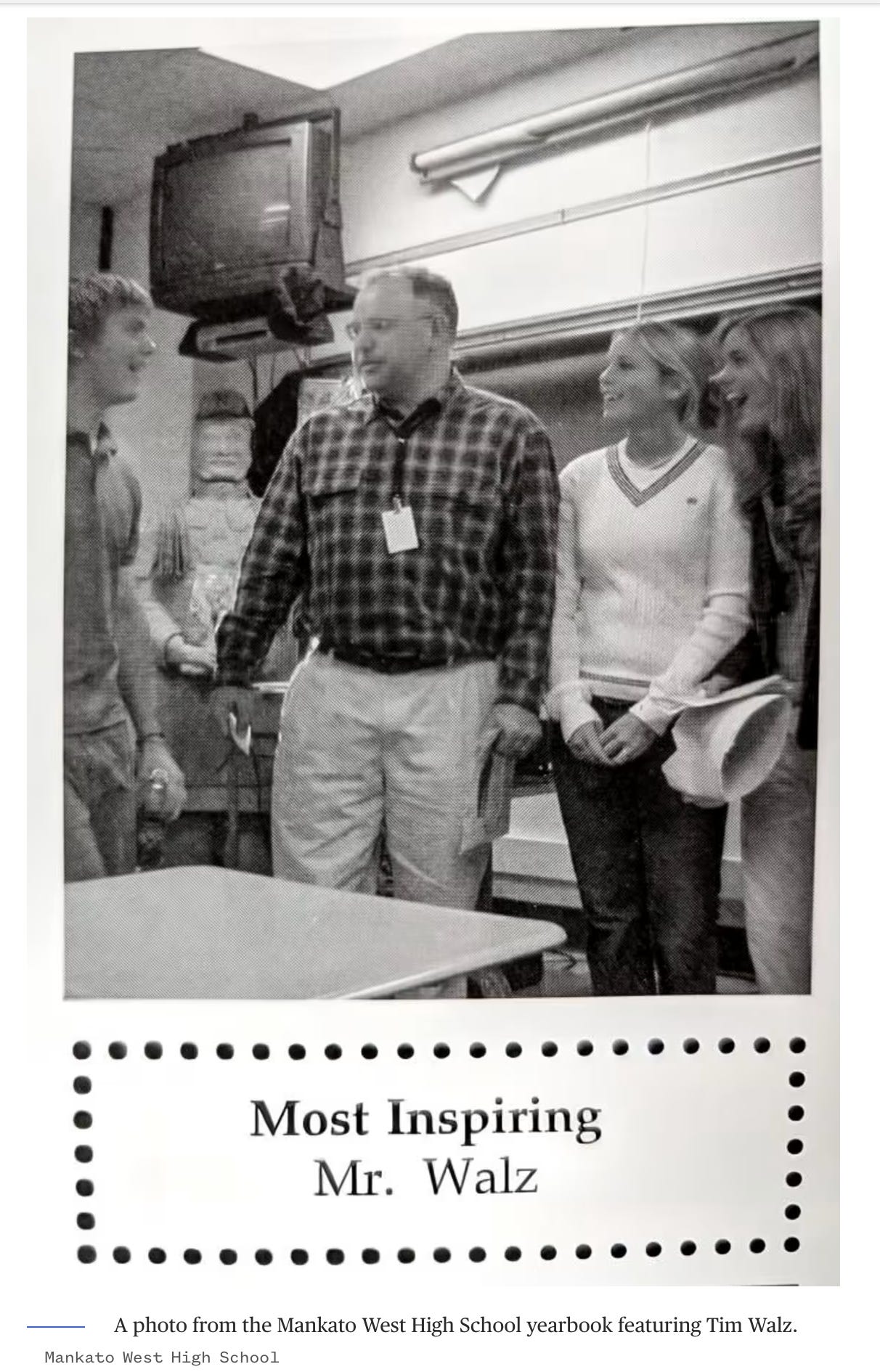

The New York Times quotes one player as saying that “if we could have thrown pads on him, he would have been out there with us.” NBC News reports he “gave out hallway high-fives, was named ‘most inspiring teacher,’ motivated students to become educators themselves and helped create a turnaround story for the football team.”

I’m skeptical of any “voted most X in high school” claims, but NBC provided proof:

What Brings You to Mankato, Mr. Walz?

Joining the coaching staff at Mankato West was Walz’s first foray back into sports after a year long self-imposed exile from athletics following a DUI in Nebraska.

Here’s what happened:

In the dead of night, a Mazda blew by a state trooper stationed in the town of Chadron, Nebraska (population ~5,600). The trooper looked down at his radar gun and his eyes surely boggled when he saw the reading: 96 mph in a 55-mph zone.

Walz thought he was being chased by a non-police vehicle, and so he sped up and kept going. It wasn’t until after the trooper remembered to turn on his lights and siren did he slow down and pull over. The cop smelled alcohol, and proceeded to conduct a field sobriety test. Walz blew a point 0.128. He was booked in county jail, and had a mug shot taken that is not as cool as Elvis’s.

He offered to resign from his position at Alliance High School. The principal would accept the resignation, but nevertheless withdrew from the sidelines.

“We all tried to talk him out of it because, in our eyes, none of us were perfect,” Mr. Rocky Almond, the head coach Walz worked with at the time, said to The New York Times. “But in Tim’s eyes, he made a mistake on something he preached to the kids.”

Tim and Gwen Walz moved to Mankato the following summer. This is speculation on my part, but perhaps Tim Walz had to be coaxed back to coaching. Maybe he was depressed, and didn’t think very highly of himself. A contemporaneous story is that Gwen Walz confiscated Tim’s Sega Dreamcast because he was playing it too much.

Perhaps she did that and egged him back into coaching. Perhaps this big, gregarious personality was the outer shell of an unhappy man—haunted by the early death of his father and/or because Nebraska and Minnesota winters suck—who was quietly looking for self-redemption and self-worth by doing right by other people.

That’s probably bullshit, but it gives him an edge and an arc and is a nice break into act two. As an aside, Tim Walz swore off drinking after the arrest and hasn’t had a drop to drink in close to thirty years.

Working with the Boss

In the pros and at the highest levels of college football, defensive and offensive coordinators can be the head coach for their side of the ball.

Coaches come up working on either offensive or defense, and when they reach the head coach position, they’ll often leave a coordinator to their own devices. Mike Ditka and Buddy Ryan, respectively the offensively experienced head coach and the defensive coordinator of the 1985 Chicago Bears, are the go-to example of this model.

But that wasn’t how Tim Walz and Rick Sutton operated.

“Tim was really great at selling his point of view and then accepting a different direction,” Sutton told the Daily Beast. “You can have disagreements, but at some point somebody has to make that decision, and that’s going to be the head coach.”

Sutton was a disciplinarian, an english teacher by trade who is routinely described in recent press reports as the bad cop to Walz’s good cop. One student described him to the hard-hitting journalists over at TMZ as “a real hard a-s-s.”

It’s pretty easy to picture the type, even if there are variations on it. Perhaps he was a screamer. Perhaps he made you do push-ups if you didn’t do your homework. Perhaps he was the type of man who could just stare at you and make you shrivel up and die. Maybe he was the type of coach who carried a simmering anger that never quite boiled over but nobody ever wanted to be the one that tipped him over the edge. The kind of man who believed hugs were earned, not given. And when they were given, they were given under protest. Surely, he was the meanest man to ever live in Minnesota.

Then you hear him do a radio interview and you realize he’s just a Fargo character.

It’s About Jimmy and Joes, not X’s and O’s

One thing Sutton and Walz clearly agreed on was that, if they were going to turn around the West Mankato program, advanced football strategy wasn’t the most important piece of the puzzle.

“In coaching, X’s and O’s are obviously are important, but it’s more about the relationships that you can build and the trust that you foster with your team,” Sutton told the StarTribune. “That’s obviously always been one of Tim’s biggest strengths. That dedication, that enthusiasm, that ability to get to know students on an individual basis is all a big part of that success.”

Just ask Dan Clement, now a business owner, then a burnout.

In his junior year, Clement was considering dropping out of school. He hung out with a crowd that was cutting class and boozing. He got suspensions. He got detentions. He got written off.

Walz felt differently.

“I met Mr. Walz at football training and he was a big fan of mine for whatever reason,” Clement told The Sunday Times (of all outlets). “I was a decent player but I wasn’t the greatest guy on the field. But I just gravitated to him and I wanted to do whatever he needed…

“Mankato was stoic, keep it to yourself, don’t get out of line. So Walz was kind of a fish out of water: big personality, outgoing, interested. He just pulls you in whether you like it or not.”

It didn’t entirely stick, though. Clement quit the team in his senior season. Walz tracked him down in the hallway between classes and pestered him to come back.

“He really pulled me along,” Clement told NBC. “He really just showed a lot of care for me to the point where I’m like, ‘OK, I’m going to continue going to school, and I’m going to work hard for you.’ I played football for him. I didn’t really play football for much of anything else.”

If that’s too trope-y for you, ask Adam Segar, who told the AP that:

Adam Segar said Walz found a spot for him on the football team despite problems he had adding weight and muscle. Segar said that approach was commonplace with Walz — trying to make sure students and athletes who might not fit a traditional mold found a place.

“I think that’s what Tim brought to small-town America was, you know, the willingness to have an open mind and ask the students to make sure that they did too,” Segar said.

Walz Ball

As for the football turnaround, Walz’s work with the linebackers was instrumental to the team’s success.

He was asked to talk about his time as a high school coach on a February 2024 appearance on the center-left’s favorite podcast, Pod Save America.

He proceeded to talk more ball than any vice presidential candidate has ever talked:

“We ran a 4-4, where we read guards at the time. I had really good athletes and good linebackers… In high school, if you pull a guard, you pretty much know where the ball’s going; and if you can teach kids to do that... [he trailed off there into another subject]”

Gerald Ford, eat your heart out.

What Walz said is relatively simple to understand, but can sound like a foreign language if you have not played organized football or Madden at least once a week for ten years.

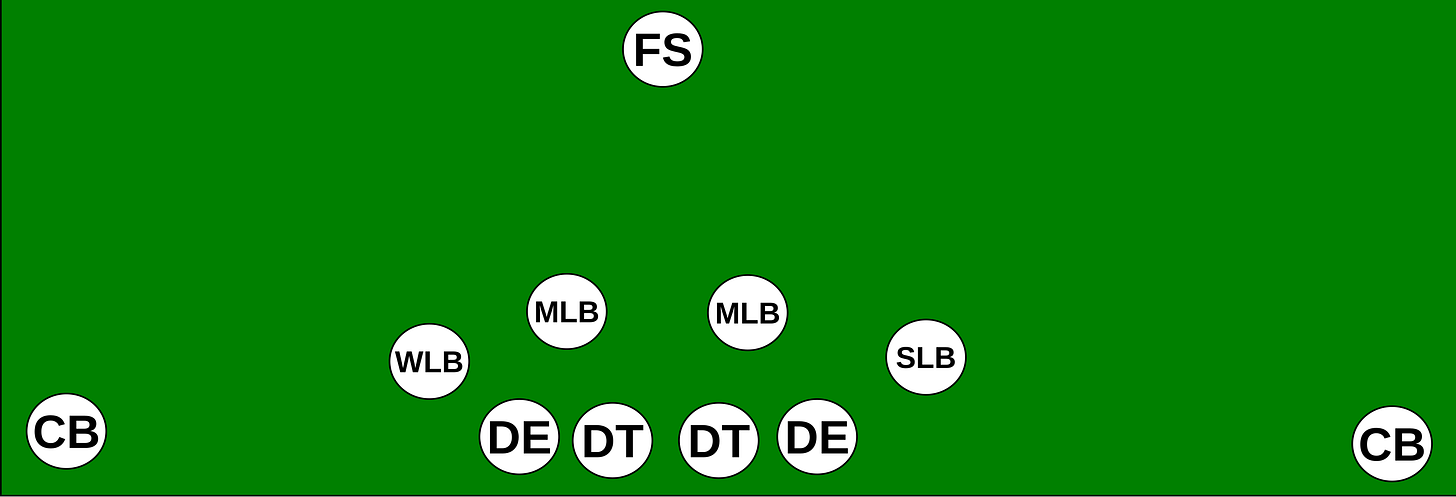

In football, defensive alignments are named after the number of defensive linemen (the big, big guys who put their hands in the dirt) and the number of linebackers (the slightly less big guys who stand behind the defensive line) that are on the field at any given moment.

On running plays, defensive linemen are supposed to muck up the offensive line, ideally blowing past them and tackling the running back, but at the very least clearing the lane for a linebacker to do the dirty work.

If you have four linemen and three linebackers, you run a 4-3. If you have three linemen and four linebackers, you run a 3-4, and so on.

The remaining players on defense are called defensive backs. They’re mostly responsible for defending pass plays which, in 1990s high school football, wasn’t something you saw all that often because seventeen year olds tend to have noodles for arm.

To put a graphic to it, this is what Tim Walz’s defense looked like on a down-to-down basis:

Don’t worry about what any of those acronyms mean. They’re not important. All you need to know is “LB” means “linebacker.”

What is also not important, but much more interesting, is understanding what Walz means when he says, “pull a guard.”

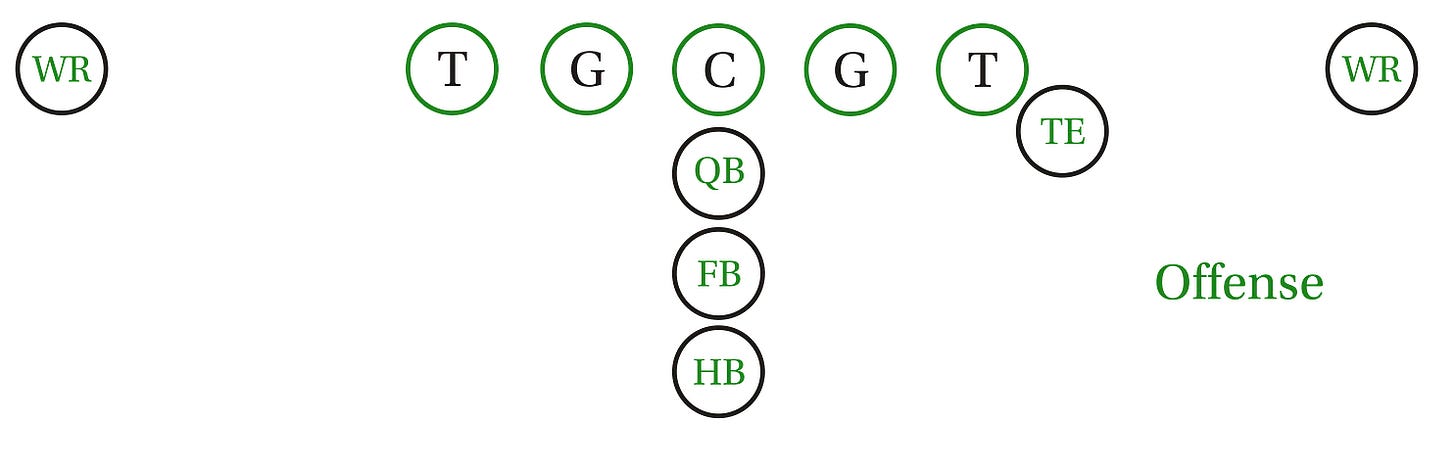

An offensive line consists of five players. The center, who is in the middle; two guards, who are to the left and the right of the center; and two tackles, who are next to the guards. When everyone on offense lined up in the 1990s, it generally looked like this:

When a guard “pulls,” he is running across the formation, behind the center and the other guard, to block for the halfback (AKA the running back), who has been handed the ball by the quarterback. This creates atypical “gaps” in the line for the running back to dash through which the defense then has to account for.

This is called a power run. When a linebacker “reads a guard,” what he’s doing is watching the guard to see what direction he moves, and then shifts his responsibility in that direction, attacking one gap further over than he would had the guard not pulled.

Football’s a simple game, (Walz had a saying, “11 to the ball”) but it can get very complicated. Take this gem of a sentence from a recent Wall Street Journal article by way of MSN.com:

According to a 1998 Mankato West playbook reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, the Scarlets’ defense had 234 variations they could run on any given play, from “BASE, LOOP, COVER 3” to “SMACK, TWIST, COVER 2.”

1999: The Unlikely Championship Season

Under Sutton and Walz, the West Mankato Scarlets broke their losing streak in 1997 (even if they reportedly did not score a touchdown for the first six weeks) then made it to the playoffs in 1998, but looked poised for a massive step backward in 1999.

They opened the season by losing four out of their six matchups. They averaged a meager 22.7 points a game, though that number was skewed by a 50+ win.

Walz explained in a Minnesota Vikings radio appearance that they’d been playing teams that were in higher divisions than they were, but at the time Walz wasn’t about to use that as an excuse.

He began to grind tape. Per The New York Times:

“He’d watch film, and he knew what it was going to take for us to win,” said Eric Stenzel, a defensive star who broke a thumb early in the season and was subsequently hailed by The Star Tribune, Minnesota’s biggest newspaper, as the “best nine-fingered linebacker in the state.”

There is no publicly available game tape of the 1999 Mankato West Scarlets (if it still exists at all), but the story is that Walz switched up the defensive approach. The team moved from a 4-4 to a 4-3 and ran a two-high safety look (a fancy way of saying that two defensive backs are going to stand far away from the line of scrimmage). I can only assume this was to counter the increasing prevalence of the passing game, and he had faith at least one of those safeties had the speed to get involved in the run game.

Walz couldn’t make this change on his own. He had to convince Sutton first. And it was a big ask. You normally need an offseason to install a new style of play. They had one week. Sutton gave it the greenlight, and the players all bought in.

The Scarlets put the new scheme, and their ability to learn on the fly, to the test in “the Jug game,” a rivalry game against Mankato East.

Bryce Tillman, then an offensive lineman for the Scarlets and now an engineer in his 40s, explained to The Sunday Times:

“West was the team that played with heart, not taking cheap shots, not trying to get away with stuff the refs wouldn’t see. East had a tendency to get away with that stuff but Walz was always very adamant about not stooping to that level. [He’d say:] ‘Keep your integrity.’ ”

The discipline held up, as did the new defensive scheme. Mankato West beat their dreaded rivals and kept the winning streak alive over the next few games, earning a spot in the playoffs by the skin of their teeth.

Eric Stenzel, who became the team’s top tackler, an All-State linebacker, and would go on to play in a reserve capacity for the University of Minnesota, told The Mankato Free Press in 2008: “Our grade group always thought we had a chance (to win a state championship)… We had to go through some struggles, but it was our senior year and we kept battling.”

Jay Nessler, the team’s senior quarterback, told the local paper in the same article: “We started 2-4, but we knew that playing in Big Nine (Conference) is tough, and we lost some tough games. Then we got on a roll, and we knew we had a shot.”

Dan Clement had graduated from the school by this point, though it would make a much better story if he was still a member of the linebacker corps. He’s say to multiple outlets that he was still with the team, but this time from the stands.

The Season’s B-Story

Jacob Reitan, now a lawyer, then a closeted teenager, was Gwen’s student. When he decided to come out to a select few, she was the third person he told.

The summer going into his senior year, he decided to come out to everyone, and that he would start Mankato West’s first gay-straight alliance before he graduated high school.

This seemed like something of a risk, and he might have been ready to fight for it. He and other students, including a young woman named Amanda Hinkle, tried to organize a human rights-focused week which included a “Gay Awareness Day.”

But some students at Mankato West did not want to be aware. They were perfectly happy not being aware, thank you very much.

Per Hinkle’s journal, which she shared with The Washington Post, “150 kids threatened to leave school if anything more was said about sexual orientation. Kids were tearing down signs that said stuff about gay tolerance.”

Don’t ask. Don’t tell. Don’t put up any posters.

But new year, new me. When school began, Reitan spoke with the school’s principal and two teachers he thought would be receptive to the idea: Tim and Gwen.

Tim decided to act as the group’s faculty adviser. He told the StarTribune in 2018: “It really needed to be the football coach, who was the soldier and was straight and was married.”

Unsurprisingly, there were objections to West Mankato’s newly formed Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA). Reitan tells AP that parents called and threatened to pull their kids out of school. The principal said, that’s fine, we’ll just mark them as absent. I have not been able to locate any press reports of an student absence epidemic.

Now, what happened next happened during the spring following the football season, but let’s pretend it happened in the fall of 1999. It makes for a better story.

West Mankato’s newly formed Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) organized another week focused on human rights. Each day highlighted various forms of discrimination. They even arranged for an all-school assembly.

In this instance, some parents did actually put their money where their mouth was, and didn’t allow their kids to go to school on the day about discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation.

Laura Matson, a student in the GSA at the time, described Tim Walz’s reaction to The Washington Post like this: “He said, ‘Some people just don’t understand, and that’s okay. We’ll keep doing what we’re doing...’”

The Streak

In 1999, Minnesota high school football’s post season was divided into two parts: sectionals, where teams compete against other teams within their general geographic area, and then a statewide tournament.

The Scarlets were hardly challenged in sectionals. They shut out their first two opponents and scored a combined 98 points against them. The section title game wasn’t much different: a 42-20 romp over the Worthington Trojans.

They were given a run for their money by the Eagles of Totino-Grace High School, a private Catholic school that is named after an archbishop and two generous benefactors: Jim and Rose Totino.

As in the Totino Pizza Rolls.

This is not a bit.

I am not making this up.

Even with the power of pizza, they couldn’t stop Rick Sutton, Tim Walz, and the West Mankato Scarlets. The Scarlets baked the Eagles, 28-16.

The semifinal game more resembled the sectional matchups. The Scarlets shutdown their opposition and filled up the end zone. Final: 45 to 8.

Now all that stood between West Mankato and a state title were the Cambridge-Isanti Bluejackets. While West Mankato was spearheaded by its All-State linebacker, the Bluejackets were powered by an All-State running back named Preston Treichel.

The Prince Bowl

The Class 4A championship game, which as far as I know doesn’t have a name so I will insist on calling it The Prince Bowl, was played in the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome, the then home of the Minnesota Vikings and the University of Minnesota’s Golden Gophers.

Much like Hubert Humphrey, no one has particularly strong feelings about the Metrodome. It was plain. Spartan. Utilitarian. A paragon of the minimalist aesthetic, if you felt like being generous. An official once said that all it was designed to do was “get fans in, let 'em see a game, and let 'em go home.”

If you’re a seventeen year old playing in a 64,000 seat arena, even if it was only a quarter full, is a spiritual experience. The scale, the echo, the bright lights that were it not for you would be engulfed in darkness beneath a gray roof propelled only by hot air, the fact you were playing on the same field as the team you watched on Sundays. The game was televised, and at least a dozen people probably watched it. The whole affair’s enough to give any kid goosebumps.

But the Scarlets did not play like a bunch of school children who were just happy to be there, aw-wow-gee-wiz. They scored on their first possession, then raced to a 21-7 lead off of a hard nosed, ground-and-pound running game.

The Bluejackets narrowed the lead to 21-14 when Calen Wilson, Mankato West’s punt returner, fumbled the ball on a return attempt. Wilson redeemed himself on his next try, zipping down the field for a 93-yard touchdown (setting a record which continued to stand as of at least 2019) and making the score 28-14.

Cambridge-Isanti would not give up, though. They drove down the field for a touchdown and then tied the game in the fourth quarter when they stripped West Mankato’s running back, Chris Boyer, at the 10-yard line and ran it back to the house.

“The [West Mankato] guys were excited because we knew we could score, and there was plenty of time,” Nessler told The Mankato Free Press in 2008. “[Boyer] definitely wanted another shot. He was one of our go-to guys, and he kept saying, `give me another chance.’”

The same way Walz’s Nebraska employers were willing to give him another shot, the same way Walz was ready to give Dan Clement another shot, the West Mankato coaching staff gave Boyer another shot.

They called his number multiple times in the ensuing drive. He rushed for 45 yards and scored when Cambridge-Isanti tried and failed to halt him on a goal line stand, making it 35-28 in West Mankato’s favor.

But there was a problem. The clock wasn’t at triple zeroes. There were around 180 ticks left. Not much, but enough for Cambridge-Isanti to march down the field and force OT.

And in what had to feel like a slow motion train wreck for Walz, Cambridge-Isanti cut through his defense and got into scoring position.

Cambridge-Isanti out coached itself, though. Echoing, the Patriots-Seahawks Super Bowl of 2015, in the most crucial moment of the game, the coaching staff told Cambridge-Isanti quarterback not to hand the ball off to their star running back. They told him to drop back to pass.

He took his drop. He surveyed the field. He threw a rocket to a wide receiver.

Either because the quarterback hadn’t seen him or thought he could dart the ball past him, a West Mankato defensive back was in position to try and make a play on the ball.

So he did.

And he caught it.

He hit the deck.

He ended the game.

The New York Times describes the next moment: “A coach lifted Tim Walz skyward.”

It was hard a-s-s Rick Sutton.

“It was one of those moments that you can’t describe unless you’ve been in it,” Sutton told The Wall Street Journal. “Big, big bear hug.”

Coach Turned Congressman

Sometime much later, long after the West Mankato football team returned home with a police escort and long after the Class 4A State Championship trophy had been safely locked in a glass display case inside the high school, Tim Walz was teaching students.

It was 2004. John Kerry was running against George “The Decider™” Bush. It was a truly insane time. The United States had just blown up a whole country looking for WMDs that did not exist. George Bush had turned gay marriage—something absolutely nobody was talking about until he was going around saying America should ban it—into a campaign issue and John Kerry’s response was harder to understand than a William Faulkner sentence. Worst of all, Hoobastank was in the Billboard Top 40.

Tim Walz may have never entered politics if he hadn’t tried to take students to presidential rallies as part of his teaching work.

It was a George W. Bush rally specifically that altered Walz’s life.

Security didn’t want the students there. In fact, they barred them entry. Why? Because one of the students had a John Kerry sticker on their wallet and The Decider™ had Decided™ he didn’t want Kerry supporters at his rally, lest they cause a ruckus by pointing out he had just blown up a whole country looking WMDs that did not exist.

This rubbed Walz the wrong way. So he went to work for the Kerry campaign, and subsequently filed to run for Congress on February 10, 2005.

Walz’s opponent was the incumbent Republican, Gil Gutknecht, who had served the district for the last 12 years. Which was a problem for Gil, because earlier in his career he had argued that congressmen should serve no longer than 12 years. He even introduced a bill to try to turn it into law, but, unsurprisingly, he found little support from his colleagues.

The geniuses in Gutknecht’s campaign sought to cover this up. Their strategy: edit Gutknecht’s Wikipedia page. And they would have gotten away with it too if it wasn’t for a meddling kid, specifically a homeschooled 15-year-old from Nashville named Daniel Bush. Daniel had no trouble identifying Gutknecht’s staffers because they were using a Wikipedia account named “Gutknecht01.”

While the media hit him on this, Walz was able to hit him on his Wall Street favoring tax cuts and his support for blowing up a whole country looking for WMDs that did not exist. Cambridge-Isanti was a tougher opponent.

Walz won the election by six points.

He became a congressman but never quite stopped being a coach.

In 2010, he caught up with Bud Pettigrew, a childhood friend and a big wig in Nebraska Democratic politics, and stepped aside to talk in private with him, drawing something on a napkin. Attendees assumed they were having an intense conversation about political strategy, but they were actually diagramming how to properly execute a counter trey.

Rick Sutton, for his part, is partially retired now. And while Walz obviously no longer coaches, he’s made appearances at West Mankato games after leaving the school for politics. He also references the 1999 season not infrequently, most notably during his COVID-centric 2021 State of the State address, which he delivered from his old classroom at West Mankato High School.

“I don’t think we would have won that state championship if we hadn’t lost at the beginning of the season,” he said. “I don’t think we would’ve won that state championship if we hadn’t lost at the beginning of the season. It taught us grit, resilience, and the true meaning of teamwork. Each player stayed in his lane and did his part to bring home that first state title. That’s what Minnesotans have done this year. It isn’t giant acts of heroism that are defeating this pandemic—it is Minnesotans each doing the right thing to the best of their ability.”

I would probably rewrite this speech a bit to include something about the human capacity for growth and redemption so it would be the perfect ending for a Disney sports movie, but then again maybe a speech discussing our collective response to COVID isn’t exactly the best vehicle for talking about the better angels of our nature.

Maybe a better ending is to talk about how after the championship, Walz supported a student named Ann Vote (this is real, I swear) as she worked on getting a prom theme approved that wasn’t in the pre-approved package the students had been handed by a school vendor. The theme? “In Our Wildest Dreams.”